Discover Python and Patterns (29): Software Architecture

In this post, I describe the organization of the tank game code. It is not the best design one could create, there are many flaws, but there are many good ideas you can use for your projects!

This post is part of the Discover Python and Patterns series

Python language and software design

The first purpose of this series is to discover the Python language. We have only seen a small part of this programming language; it contains many other features. Anyway, we have seen enough to create a small game :)

Considering this subset of the Python language, if you are a beginner, it should be a bit fuzzy. I hope that you understand some basics like creating a variable and assigning a value to it. For other features, maybe it looks magic and works for unknown reasons.

You should not worry about this. Learn programming, and especially syntax, take time and can't be acquired after reading a single tutorial. Even if someone was telling you every syntax rules of a programming language, it is impossible to memorize all of them in a row.

To learn a programming language, it is easy: practice. Try to create small programs, read tutorials, and after a while, you will master the language.

For software design, which I want to emphasize in this post, it is different. There is not a lot of rules, and anyone can quickly memorize them. However, understand these rules and develop an intuition around them is much more difficult. Practicing also helps, but in the first place, we need to get a deep understanding. If one day you have the feeling that software design is always doing the same, it means that you are in a good way :)

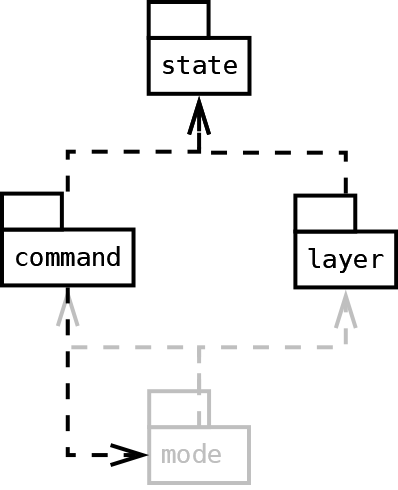

The big picture

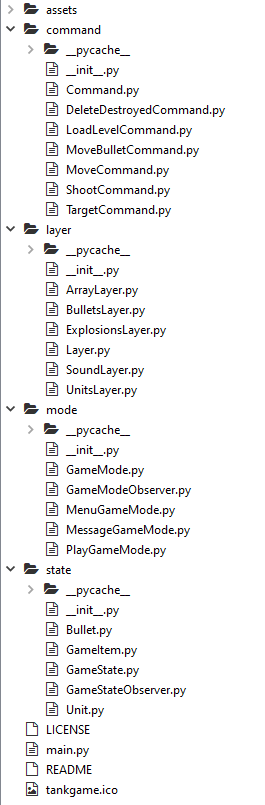

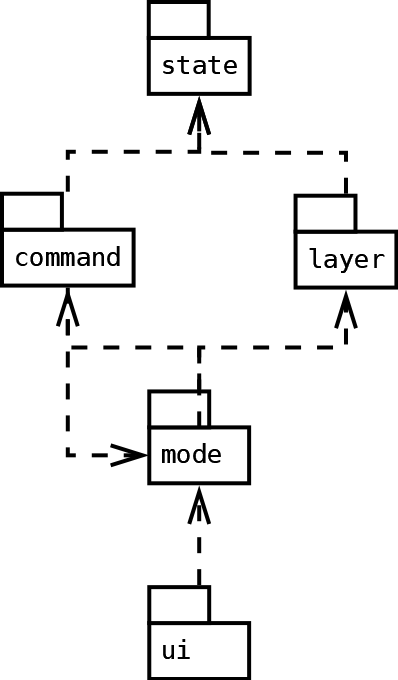

Let's see how I organized the tank game:

There are five main components:

state: it contains the game state, in other words, all the data required to represent any possible state of the game. For instance, units, bullets, world items, etc.command: it contains the game rules. These rules allow us to update the game state in some way. More specifically, it includes the command classes that, once applied, change the content of the game state according to parameters. Note that it does not tell what changes to trigger.layer: it contains the rendering procedures. There are several layer classes, each one dedicated to a specific case, like rendering a background or animating bullets. Note that it does not tell what to render; someone else must combine these layers to create a scene.mode: it contains the different modes or sub-games of the game. One of the modes is the main game, and others are cases like a menu, a map, an inventory, etc. It uses the other components to create and combine objects that form sub-games.ui: it is the final component that contains all game modes and manages them.

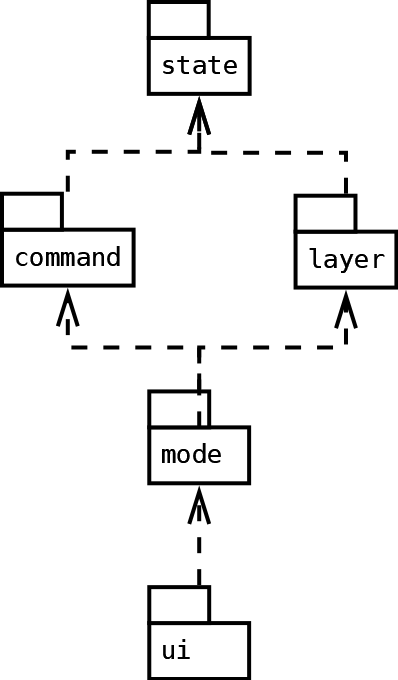

Dependencies

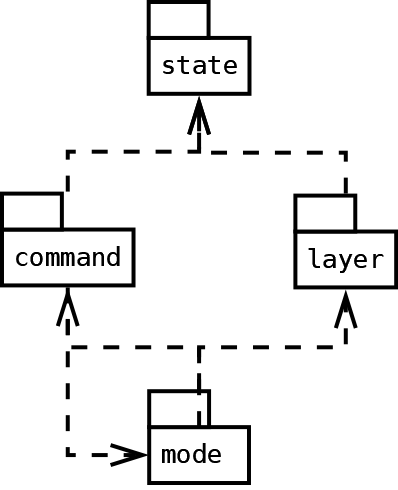

The less dependencies, the better the design

On the diagram, you can see arrows. They represent dependencies. For instance, the command component depends on the state component (the arrow points state), and the state component does not depend on the command component. These arrows allow us to have a quick view of component dependencies.

As I told you many times in this series, software designers don't like dependencies and especially circular dependencies. The more dependencies there are, the more difficult it is to split parts of a program. For a thousand reasons which I started to present in this series, the more we divide our code into independent components, the easier it is to maintain and expand it.

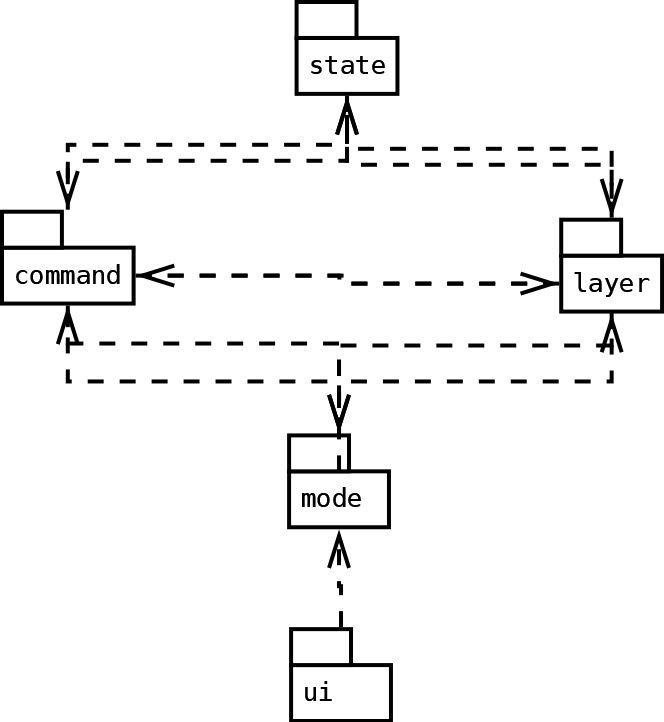

A software designer nightmare could look like this:

Most components depend on all the others. If we have to change something in one component, there is a high chance that we have to update all other components. In a small program, we can handle this, but on a large one, it is a tough problem.

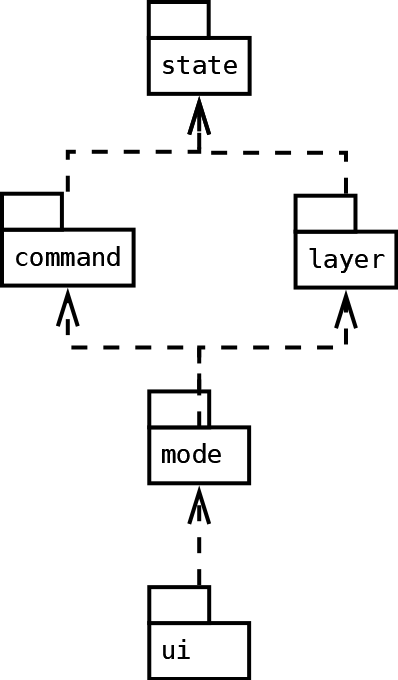

Dependencies tree

On the proposed architecture, dependencies form a kind of tree:

The state component is the root of this tree. It does not depend on another component. You can delete everything else, it still works.

Then, the command and layer components are the first branches of this tree. They are independent: we can create one without the other. In both cases, we must use the state component; otherwise, they can't work.

The mode component depends on the command and layer components: if one is missing, we can't use it. Since these two dependencies depend on state, it means that mode also depends on state. We don't draw an arrow between mode and statebecause we can easily see it: just follow the direction of arrows from mode to state.

The ui component depends on the mode component, and consequently, on all the components of this architecture.

A flaw!

The code I proposed in the previous post does not respect these good dependencies. If you have a look at the LoadLevelCommand class, you can see that it needs an instance of GameMode.

As a result, the diagram of this code is:

There is a circular dependency between command and mode. It is not good!

Note that I left this design error for several reasons. Firstly, solving it leads to more complexity in the final design, which is maybe already too complicated for beginners (I hope not!). Secondly, it shows you a true case of bad design, which is always good to see in practice rather than only in theory. And finally, it is a good exercise: try to find a solution! Note that if you only find why it is an issue, and what should be in which place, you mostly solved the problem.

The state component

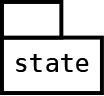

Let's begin the detailed description of this design with the core of our program: the game state component. It can "live" alone, and exists without any other component:

The classes inside this component are the following ones:

The GameState class is the main data container. It contains several lists of items. For simple ones, like the ground tile, we can use existing classes, like Vector2 in Pygame.

For more complicated items, we created a small class hierarchy with GameItem as the base class, and Unit and Bullet as child classes.

Finally, the GameState follows the Observer pattern and can contain references to observers as child classes of GameStateObserver.

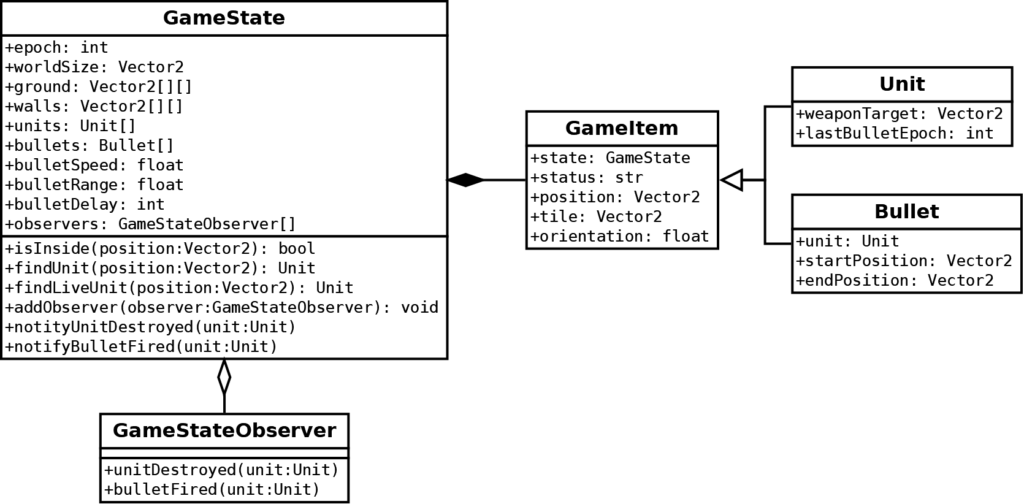

Python modules

In the previous post, all code is in a single file. It is relevant when presenting small programs, but become problematic with large ones.

A common solution consists of splitting the code into several files with one file per class. Furthermore, we put all classes from the same component (or module or package) in the same directory.

For the state component, all files are the following ones, and we put them in a "state" directory:

Note: in Spyder you can see files and folder with the "File Explorer" (Menu View / Panes / File Explorer).

In this screenshot, you can see two unexpected items: the __pycache__ folder and the __init__.py Python file.

The __pycache__ folder is created by Python to speed up compilation and execution. It is automatic, don't pay attention to this folder (if you delete it, Python will recreate it).

The __init__.py is a new file I added with the following content:

from .Bullet import Bullet

from .GameState import GameState

from .GameStateObserver import GameStateObserver

from .Unit import UnitThe first purpose of this file is to tell Python that this folder is a module. A module is a set of features that we can import from other modules.

The second purpose of this file is to add code that helps the use of this module. In our case, I declared the relevant classes to ease its import from outside.

For instance, to import the GameState class without this trick, a user has to type:

# In a file outside the state folder

from state.GameState import GameStateThanks to the following line in the __init__.py file of the "state" folder:

# In the "__init__.py" of the "state" folder

from .GameState import GameStateA user only has to type:

# In a file outside the state folder

from state import GameStateIt also prevents other problems I don't describe here. As a rule of thumb, you should always create this file with such declarations. It will ease the management of your program.

Perhaps you wonder why there is a dot . in these declarations. It tells Python to search in the current directory rather than searching from the root of the program. Otherwise, you must put the full file "path", for instance from state.GameState import GameState. It is handy if you move the classes (usually in sub-sub-folders) when the program grows.

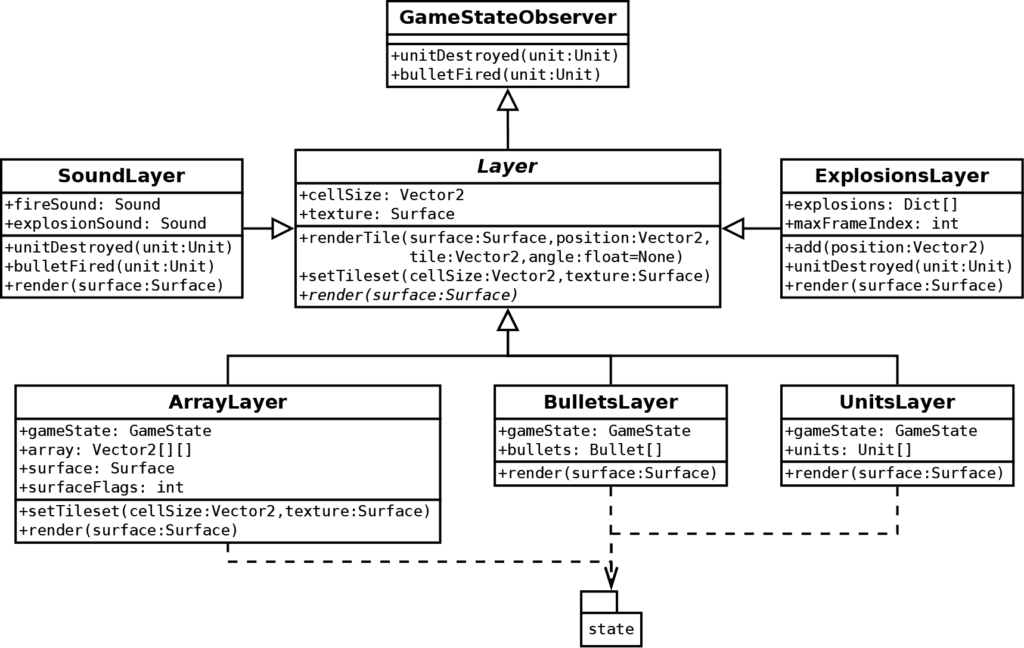

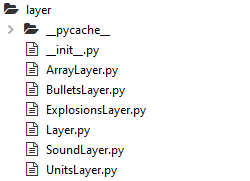

The layer module

Now that we have seen Python modules, we can talk about the layer module. In other languages, people talk about packages.

The layer module only depends on the state package:

The classes inside this component are the following ones:

There is a class hierarchy, with GameStateObserver the main base class, Layer the intermediate base class, and all other ones the child classes.

Consequently, all classes depend on the GameStateObserver which is a class inside the state module, so the layer module depends on state module.

However, only the classes ArrayLayer, BulletsLayer and UnitsLayer depends on many classes of the state module, which I represented by a mini package. We can quickly see that we must pay attention to these classes when the state components are updated. For the others, we can ignore it.

I also split the code into several files and put then in a "layer" folder:

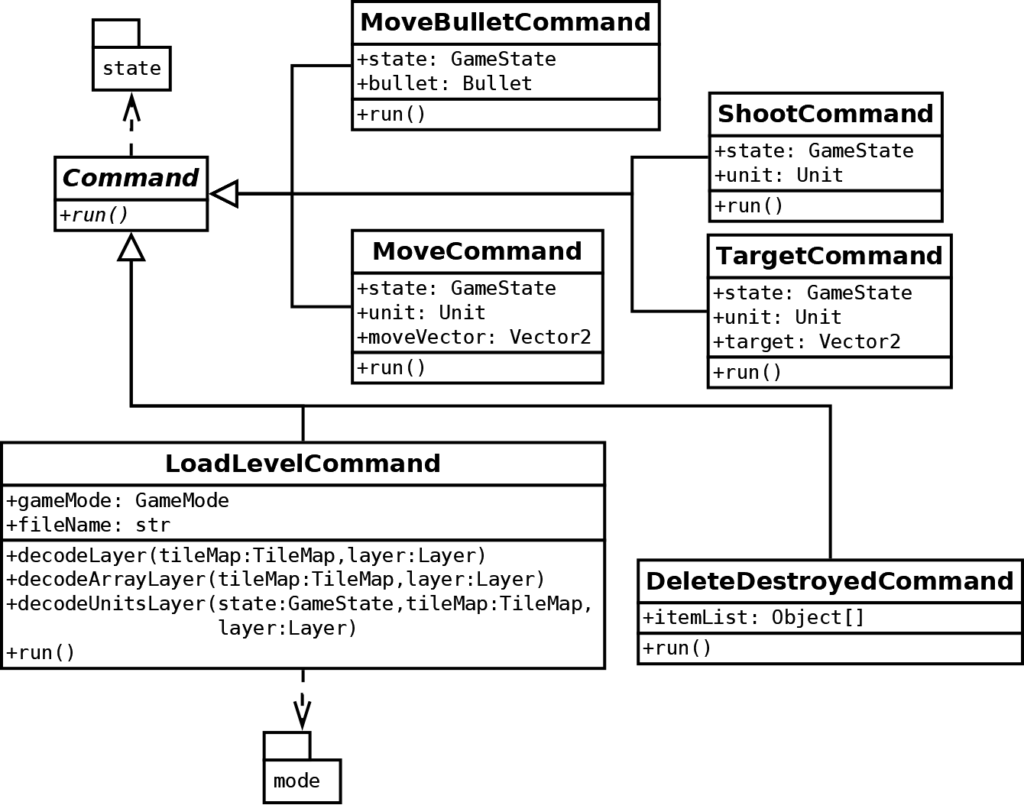

The command module

The command module depends on the state package... and on the mode package:

As presented earlier, it is a flaw in our design. We can better see why in the class diagram:

It is also a class hierarchy, whose base class is Command. To represent the dependencies of all child classes to components of the state module, I added a mini state package.

We can see that command depends on mode because of the LoadLevelCommand class, which needs a reference to a GameMode class.

Load a level is an in-between procedure. It updates the game state, as for any command. It also updates the rendering layers of the main game mode. If we have to run the game updates on a server with no screen nor controls, it will not work!

Since only commands should change the game state on the one hand, and should not depend on rendering, on the other hand, we can't put this procedure in any current module without changes.

Try to find a solution: you can create new commands, or new modules, or reuse patterns we saw, like the Observer pattern.

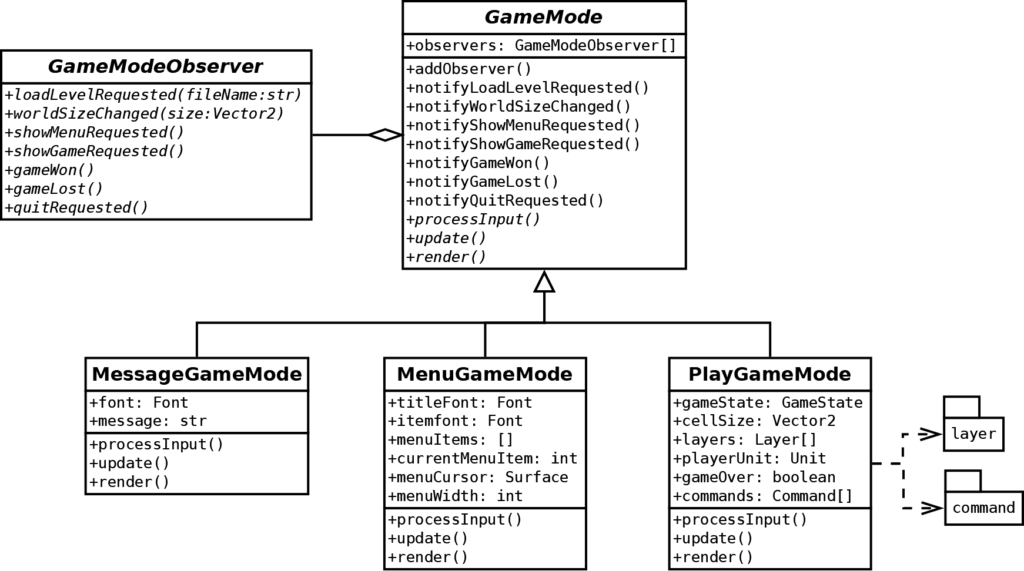

The mode module

This module depends on all the previous modules:

The classes inside this component are the following ones:

It is also a class hierarchy with the Observer pattern.

We can see that only the PlayGameMode depends on the other modules. It means that we can modify the menu and messages without worrying about the changes in the main game components.

Final code

A final main.py contains the UserInterface class, and an assets folder contains all assets: